11 May Let’s Twist Again – Those Pesky Ankle Sprains

The subject for this blog is ankle injury; in particular, the typical twisted ankle. Everyone has probably experienced this at some point, whether from sports, slippery surfaces, or simply missing the kerb.

The most typical damage caused by twisting an ankle is an inversion sprain, whereby the lateral ligaments that hold the ankle secure are overstretched and cause considerable pain. Whilst these injuries vary from minor to serious, an issue commonly raised by patients is how often they repeat.

We commonly hear stories of repeated ankle injury when quizzing patients who present with low back pain, for example, also when we meet patients presenting with knee, hip or even shoulder injury. Patients have often put a brave face on, coped with the pain via strapping and ice, and waited for things to settle before returning to activity. Only for it to happen again. Why is this?

A Design Issue

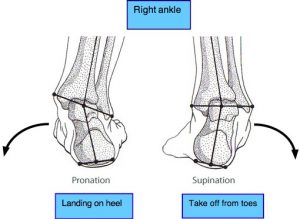

When our foot contacts the ground, it must be in a balanced position so that forces pass safely from the foot through the ankle, and up the leg to the pelvis and into the torso. Life on flat ground is easy, but many surfaces present more of a challenge. However, the mobility that we have in our ankle joint to cope with undulating terrain leaves it potentially unstable.

The talo-crural joint is the main ankle joint, and is formed of a mortice of tibia and fibula over the talus

The main ankle joint is called the talocrural joint and is formed between the bottom of the tibia and fibula (the long bones below your knee), and the top of the talus which is mostly hidden inside the ankle.

The tibia and fibula fit over the top of the talus, forming a mortice. But as the talus rotates up and down inside this mortice, the wedge-shaped joint surface on top leaves the joint with more free play when toes are pointed than when your foot is pulled up towards your body. So those high heels that force you to walk almost on tip toes are leaving your ankle in a less stable posture, and therefore the risk of injury is raised. In contrast, when your foot is flat on the floor, the joint is held tighter as the talus wedges itself backwards into the mortice.

There’s More…

We also have a second ankle joint below the joint we’ve just looked at. This joint, called the subtalar joint, allows the foot to rock from side to side. This is useful for dealing with uneven surfaces. You might think this joint is to blame for ankle sprains, allowing your foot to roll excessively from side to side, but in reality, it’s a sturdy joint held together by some strong ligaments deep between the bony surfaces.

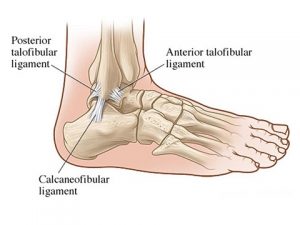

In contrast, the external ligaments of the ankle are vulnerable. These pass from the tibia and fibula, attaching to the talus and also to other bones of the foot. This means that they cross over both the talocrural and subtalar joints. When the ankle is forced to move beyond its safe range, it is these ligaments that get overstretched and become damaged.

By now, you probably get the idea that the ankle is quite a complex piece of kit, and we’ve not even talked about the necessary mobility through the bones of the midfoot, the importance of the big toe, or the plantar fascia and windlass mechanism!

It’s all about stability

Now we’ve explained the bony structure of the ankle, it is the muscles that we must look to for true support of daily activity. We’re probably all aware of the large calf muscles that lift us up on to our toes via their connection through the Achilles tendon. There are also muscles that pull the foot backwards and can cause shin splints when they’re overworked.

Of interest when we are considering twisted ankles are the peroneal muscles, also known as the fibular muscles. These muscles attach to the fibula and run down the outside of the lower leg before attaching to the lateral foot and wrapping underneath it to attach to the sole of the foot. Their function is to pull the foot upwards, but more importantly to evert the foot, pulling the sole foot outwards.

Importantly, the function of these muscles is what often protects us from inversion sprains, since they control motion of the ankle in the opposite direction. Therefore, an important focus of rehab for ankle injuries is strength and activation of these muscles. Without patients doing any rehab after injury, these muscles will activate poorly, and leave patients vulnerable to repeat injury.

So, the answer to those patients who struggle with repeated ankle sprains is for them to persist with rehab past the stage where the pain has gone and walking is pain-free. The ankle must be challenged in more dynamic situations so that it becomes fully competent again.

It’s all in the timing

So why is it not enough to just be pain-free and walking around again? The answer is in the nervous system. Sensors in our ankles must report the position of the joint, whether it’s tilted left or right, toes pointed down or up, and send information to the brain. The brain must then figure out whether it likes what it’s hearing, and decide whether to engage muscles to pull us out of the position we’re going into. Simple, no?

However, the time it takes for the brain to recognise that the ankle is moving towards a tricky position is longer than it takes us typically to slip on that banana skin. It’s all very well being able to slowly move your ankle about under good control, but when injury strikes, it tends to happen so quickly, that we’re unable to do anything to prevent it. So why bother training the muscles if they’re always going to be too slow?

Like the scouts – always prepared

The deal with ankle stability is really the same as core stability (and rotator cuff activity while we’re at it). Having strength in the muscles is great, and there’s always going to be a minimum requirement, but the real trick in lowering injury risk lies in having the muscles active BEFORE they’re required. They don’t need to be clenching for all they’re worth, but just need to be gently working to show they’re ready for action.

This means that after the basic exercises to obtain pain-free movement and start strengthening muscles, more involved rehab should involve complex movements and weight-bearing work. That way, the muscles get used to being active with bodyweight on top of the ankle, yet still in a controlled manner.

Patients should also have plenty of balance work, and a staged progression through increasingly complex movements, jumping and running, all the way up to what they demand. This way, there shouldn’t be any shock to the ankle on a return to activity, and patient confidence should be high whether they’re taking part in sport, walking the dog, or donning those high heels for a night out.

The other injuries…

This blog has discussed lateral ankle sprains, but it’s important to appreciate that whilst these are common injuries, there are many other causes of ankle pain. There can be injuries to many other ligaments or problems with tendons and the sheaths they pass through. There can even be minor fractures that slip the net since many are too fine to show on an X-ray taken immediately after an incident (they show better after a few weeks of healing). So in conclusion, we always advise that patients get assessed by a suitably qualified practitioner to ascertain the type of injury and make an assessment of the severity.

If you have any questions or need help with a niggling ankle injury, please call the clinic and we can arrange a consultation with one of our practitioners to start guiding you through this process.

Toby is an osteopath at OpenHealth, and regularly contributes to our blogs.

No Comments