02 Oct Core Blimey – 7 Myths about your Core

Many of our patients, especially those with low back pain, are concerned that they have weak core muscles, and that weakness in this area has either contributed to their current pain or will predispose them to more pain in the future.

This is a topic that has been subject to a lot of scrutiny, and more importantly, has seen opinions change over the last 20 years. We have moved away from the notion that building strength and rigidity through the low back will prevent pain, and instead now understand that to control and prevent low back pain, we need mobile joints with a dynamic support system that offers a variety of solutions to different scenarios.

What do we mean by this?

Suppose you’re asked to pass the salt over the dinner table. If you’re in pain, you might decide to tense your abdominal muscles to prevent too much motion through your low back. This seems sensible in the early days of an injury but is this wise long-term? It might be fine to tense all those muscles to move a barrel of beer, but to lift a salt shaker? That can’t be right!

So, let’s have a look at some of the myths surrounding this topic.

Myth 1: Your Core is Your Stomach

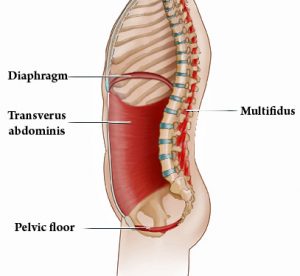

Wrong. The core is a set of muscles that form a closed capsule. The diaphragm is the roof, the pelvic floor muscles are the floor. Some of the muscles around our spine are included since they form a posterior wall. Lastly, wrapping around our sides and across our stomachs we are interested in a muscle called transversus abdominis. This muscle wraps around us with horizontal fibres.

Note that we are NOT including the rectus abdominis, more often referred to as the six-pack muscle. This muscle, made of vertical fibres, is important for bending our body forwards but doesn’t play any significant role in core stability.

Myth 2: Your Core Must Always be Tensed

Not so simple! In reality, we would hope that core muscles are activated whenever we move, but it shouldn’t be a conscious decision to make them tense, nor should they always tense to such a degree that they make you stiff. It’s all about scenarios.

Lifting a cup of tea shouldn’t require much in the way of core activation, but perhaps reaching forwards for a biscuit might require some gentle stabilisation of your spine so you don’t collapse forwards across the table!

In contrast, if you had to lift a beer barrel it would be more appropriate to brace your low back and add some temporary stiffness in order to manage the load. Once you’re done, however, those muscles need to settle back down to a relaxed state, otherwise, you’d end up stiff and brittle.

So, there’s no one answer. Instead, the body should behave according to the scenario it finds itself in.

Myth 3: The Stronger your Core, the Better

Perhaps, but the spine is strong to start with! The anatomy is very robust: large, chunky bones, bound together with very strong ligaments, and with heaps of muscles attached to all the surfaces. This design is perfect for carrying loads and absorbing forces.

At the same time, the lumbar spine is designed to move. A healthy low back can bend forwards and back, bend to the left and right, and also rotate each way. The movement is quite small between each pair of vertebrae, but the total movement of these joints added together is what matters.

Furthermore, and contrary to what many think, it’s really quite hard for the bones in our back to get out of position, and also fairly rare for discs to get damaged and allow material to get where it shouldn’t go. So, it’s a pretty sturdy structure.

Myth 4: The Core Protects the Back

Well, it does to some extent, but really, the core muscles and spine function as one system. The core muscles grip and strengthen the middle of our bodies to help us cope with heavier loads and prevent excessive movement of the joints, but this process also prevents natural movement and creates stiffness through the spine.

If anything, it is our brain that protects our lower back, since the area is obviously very important to us. To this end, the whole area is packed with nerves reporting joint position to our brains, and in return controlling the muscles very carefully.

Myth 5: The Core Always Helps

It might do on a good day, but when we have back pain, things can go haywire.

When our low back gets damaged, the brain gets bombarded with signals telling it something is wrong. It makes a plan of action and typically tenses all the muscles in that area, bracing our joints so they can’t be moved. This is quite sensible in the short term, as we want to prevent further injury.

In most cases, a patient’s damage recovers well. Their pain lessens and any threat of further injury diminishes. The muscles around their low back relax, movement increases again, and their body reverts to taking each scenario as it comes.

However, if a patient’s pain persists, their brain will still consider there to be a potential threat should it allow too much movement to occur. In these scenarios, it will continue to brace the low back and potentially create long-term stiffness.

When judging whether stiffness is better than mobility, think about which trees get blown over in a gale!

Sadly, this vicious circle of perceived threat and a bracing response can persist beyond the point where the original damage has recovered. This commonly occurs if patients have poor beliefs about the nature of their back pain, or have heard negative stories from friends, family or even medical professionals.

At this point, the way in which the core muscles are responding to the threat of pain is more relevant than any underlying damage that started it all off! Think of an ankle sprain – it’s more than reasonable to walk with a limp for a few weeks, but if you’re still limping after a year, then the limp, not the ankle, is now the problem.

Myth 6: Sit Ups Will Make Your Core Strong Again

Sorry, no. Sit-ups are great for the rectus abdominis muscle that we mentioned earlier, but this muscle is not involved in core activity. Instead, we need to find exercises that replicate the function of the core and that can help us move away from the common habit of always bracing when there’s no need to. To do this, we need to understand how the core actually functions.

Let’s imagine you’re sitting nice and tall on a bar stool, legs tucked under you, head directly above your pelvis, and you have no pain. At this moment, there isn’t really much requirement for your core to activate. You’re sitting still on a stable surface, and your posture is such that the natural curves in your spine are allowing you to sit upright with minimal muscle effort.

Now imagine that you decide to lean forwards towards a cup of tea. As soon as you move away from a nicely balanced position, it’s not unreasonable for the muscles around your low back to secure the area so that you stay in a safe posture. This is core activation! It happened automatically, and with just enough tension to stabilise you.

If we add more weight, the core will probably activate a little more to increase the bracing. And if we deliberately destabilise you by sitting you on an exercise ball instead, the core might be gently working away before you even reach for your tea, since you’ll need to keep your spine balanced even at rest.

Myth 7: Good Core Exercises Make Your Core Strong

Not really! The key in choosing core exercises is to introduce movements that require the core muscles to activate. And take note of that order! Movement should cause stimulation of our nervous system so that the brain’s only sensible response is to activate the core muscles.

Exercises that function the other way around, gripping muscles and then moving, are just not as natural. They might make certain muscles stronger, but we’re not tapping into the system that we want to address.

In summary, we need to find activity that is rich in core activation, rather than only seeking out and striving for core strength. In the right environment, the core has to work, and it will do.

The Conclusion?

This is a massive topic, and this blog has covered a lot quite quickly! Perhaps the two key things to remember are:

1. The body needs different strategies for different tasks. Remember the cup of tea vs the barrel of beer.

2. If the body feels threatened by a movement because it is painful (even if it decides this before it moves), the nervous system will tend to favour bracing, making us stiff and perhaps brittle. This might be fine in the short term, but in the long term we lose our ability to switch strategies.

What Can I Do to Help my Low Back and Core?

If this article has been of interest to you, you might want to consider seeing our Pilates instructor Laura Flanagan for some 1-to-1 sessions. Pilates is a great way to re-educate your core activation, especially since you have the option of having it taught to you face to face, with enough time to identify your movement habits and find ways of addressing them.

Similarly, we also have two great rehab specialists, Darryl and Chris, who through their approach to training the whole body are able to identify areas of sub-optimal function and help correct movement patterns.

Alternatively, if you are still overcoming an injury, our osteopaths and physiotherapists are here to assess any relevant damage and then begin the journey through your rehabilitation. Additionally, one of our osteopaths, Toby Pollard-Smith, works using a system of rehabilitation called JEMS which is designed to help patients through the processes described above.

Toby is an osteopath at OpenHealth, and regularly contributes to our blogs.

No Comments